2023 – Volumi – GALLERIA GABURRO – Milan

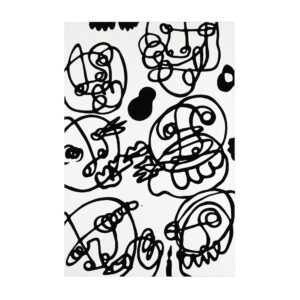

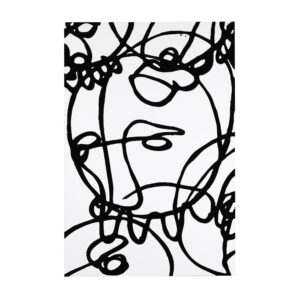

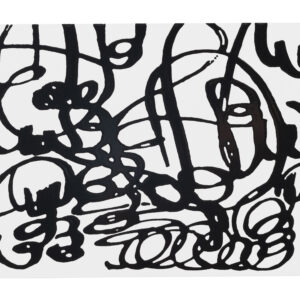

- VOLUME 005 130X200 resina e smalto su tela 2022

- VOLUME 012 130X200 resina e smalto su tela 2023

- VOLUME 006 130X200 resina e smalto su tela 2022

- VOLUME 001 150X100 resina e smalto su tela 2022

- VOLUME 002 150X100 resina e smalto su tela 2022

- VOLUME 003 150X100 resina e smalto su tela 2022

- VOLUME 004 150X100 resina e smalto su tela 2022

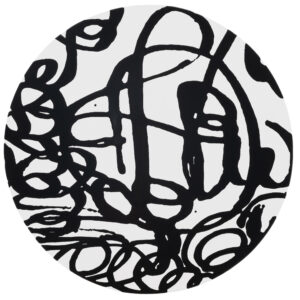

- VOLUME 014 diametro 90 resina e smalto su tela 2023

- VOLUME 015 diametro 90 resina e smalto su tela 2023

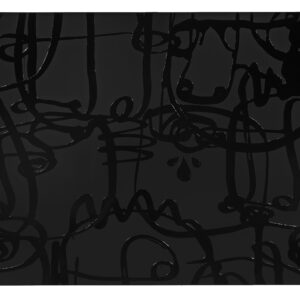

- VOLUME 011 2 200X300 resina e smalto su tela 2023

- VOLUME 016 80×80 resina e smalto su tela 2023

- VOLUME 019 200×300 resina e smalto su tela 2023

- VOLUME 021 80×80 resina e smalto su tela 2023

- VOLUME 022 50×70 resina e smalto su tela 2023

- VOLUME 023 50×70 resina e smalto su tela 2023

- VOLUME 013 50X70 resina e smalto su tela 2023

- VOLUME 018 40×50 resina e smalto su tela 2023

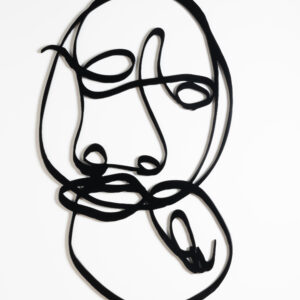

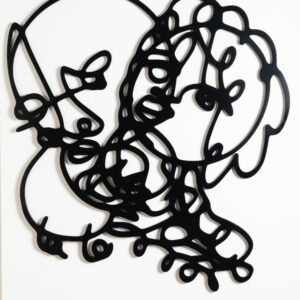

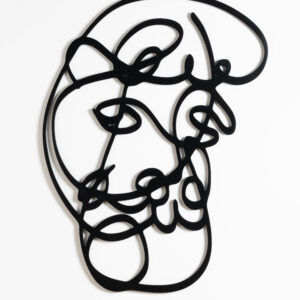

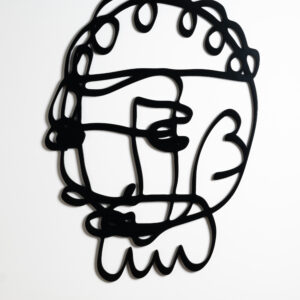

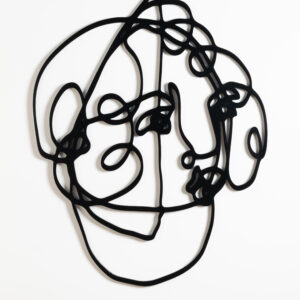

- V01-2023 smalto su legno 80X60x1

- V02-2023 smalto su legno 93x54x1

- V03-2023 smalto su legno 97X59x1

- V04-2023 smalto su legno 80x68x1

- V14-2023 smalto su legno

- V13-2023 smalto su legno 82x53x1

- V12-2023 smalto su legno 82x53x1

- V11-2023 smalto su legno 80×61

- V10-2023 smalto su legno 80×60

- V09-2023 smalto su legno 87x68x1

- V08-2023 smalto su legno 100x64x1

- V07-2023 smalto su legno 70x55x1

- V06-2023 smalto su legno 71x63x1

Il suono della pittura

1. Rime, ritmi

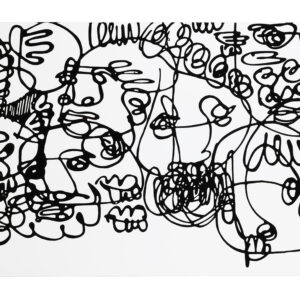

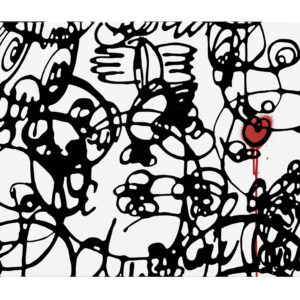

L’opera di Danilo Bucchi, apparentemente semplice nella sua immediatezza, ci pone tuttavia di fronte a complessi problemi concettuali. Innanzitutto, di fronte a una difficile domanda: come far sentire la pittura oltre i rigorosi modelli del visibile e permettere che, allo stesso tempo, la si possa ugualmente avvicinare alla percezione del suo volume andando incontro a una dimensione tattile, quasi scultorea, ma anche alla nostra memoria della musica e del ritmo, cercando in essa un’esperienza di ordine musicale?

Infatti, nelle sue molteplici espressioni — installazione, fotografia, pittura o anche nei lavori di carattere digitale — l’artista ritorna sempre in una modalità che possiamo designare come di natura ritmica, che ci permette di percepire la sua intensa relazione con una notazione di carattere musicale. È così che ogni gesto, ogni segno, ogni movimento del corpo — perché è di registri del corpo che di fatto parliamo — che si proietta sulle superfici e che troviamo costantemente nel suo lavoro, si segnala come forma di una gestualità vicina all’improvvisazione, alla notazione musicale e persino alla poesia concreta, che rivela, contemporaneamente alla capacità di muoversi verso i giochi del caso di John Cage, un forte indice performativo: come, a questo proposito, ha detto Achille Bonito Oliva “Oltre ci sono gli imprevisti della vita e le forme nella sua creatività”.

Così, quello che percepiamo subito al primo contatto che abbiamo con la sua opera ci rimanda invariabilmente a un senso percettivo che, attraverso il nostro corpo, comprendiamo essere anche originario dal movimento di un altro corpo, funzionando quasi come in una dimensione performativa. Infatti, il lavoro dell’Artista, la sua gestualità elegante e sottile, che ci sembra quasi equivalente a una modalità di scrittura — il che, su un piano erudito, evoca Cy Twombly ma anche Henri Michaux e che ugualmente dialoga, a un altro livello, con gli stessi graffiti che inondano le strade delle nostre città — presuppone, nella sua esecuzione, un movimento performativo del corpo e una forte iscrizione del gesto nel dipinto, che tende a renderlo immediatamente dell’ordine dell’avvenimento.

Perché in realtà, questa gestualità, per quanto discreta e quasi capricciosa ci sembri, con la sua strutturazione di spazi il cui carattere è, per così dire, barocco, implica un avvicinamento allo spazio della pittura che richiede al corpo di compiere una gestualità propria, nell’improvvisazione, capace di un movimento d’iscrizione che, come Bonito Oliva aveva così ben compreso, lo trasporti fino a una dimensione che è, prima di tutto, vitale. Ma determina anche, nella sua comunicazione, una presenza quasi invisibile, tuttavia sensibile, di un’economia di ritmi e rime che costantemente conducono le forme del disegno fuori da loro stesse, generando uno spazio ambiguo poiché popolato da una specie di calligrafia febbrile.

Una pratica di ordine poetico che in verità avvicina il suo lavoro, sebbene in modo lontano, a quella grande tradizione di automatismo che, da Mirò a Pollock o da Henri Michaux a Jean Dubuffet e più tardi ad Alechinski, ha definito una nuova forma di relazione tra immagine e segno, tra pittura e scrittura, relazione potente fondata sulla nozione di ritmo che il XX secolo ha costantemente reintegrato, comprendendo la necessità di tornare alla fonte arcaica, quando non al riferimento geroglifico.

2. Il momento egizio

È stato il filosofo italiano Mario Perniola a insistere già sulla possibilità di un effetto e anche di un momento egizio nell’arte e nella società, per cercare di spiegare in questo modo alcuni segni tipici della contemporaneità rilevando, attraverso tale designazione, la presenza simultanea di più temporalità coabitanti nel tempo attuale, cosa che il filosofo considerava essere ugualmente una caratteristica della cultura arcaica egizia: “Se tutto può essere arretrato, nulla è attuale, e allo stesso modo tutto è repertorio, perché tutto può diventare immediatamente presente ”.

Così possiamo dire che l’opera di Bucchi inscrive qualcosa che è dell’ordine di un momento egizio poiché in esso misteriosamente convergono presenze che non solo la collegano al suo stesso tempo — in particolare nei modi in cui assume il rapporto con la fotografia, i linguaggi dell’installazione o anche le intensità del digitale — ma ugualmente dialogano con numerose altre fonti visive.

È in questo modo che le sue opere si legano sottilmente a innumerevoli artisti di vari secoli prima del nostro, attuale: come accennato in precedenza, dall’arte barocca al XX secolo, i collegamenti sono molteplici poiché la sua opera mantiene relazioni inaspettate con Pollock, con Saura, Michaux, Dubuffet o perfino con il graffitismo urbano attuale.

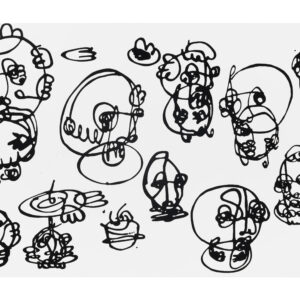

Perché, però, citare qui il barocco? Se prestiamo un po’ di attenzione alla sua modalità di costruzione interna, vediamo subito che l’opera di Bucchi inscrive costantemente queste variazioni, quasi come filigrane, in cui la linea si sviluppa come se danzasse nello spazio totale di cui dispone. E se secondo Wolfflin, la linea era più un segno tipico del classicismo che del barocco, essendo questo risultante dalla macchia, il fatto è che in queste numerose linee che si muovono incessantemente nel suo lavoro, in una gestualità che esita tra la figura e l’astrazione più pura, l’artista fa apparire la suggestione della macchia, dall’impulso nervoso di questo movimento. Non tanto perché cerca la macchia, ma questa si fa presente, sebbene costantemente esitante tra i neri e i bianchi.

Barocco è, quindi, questo scintillio nervoso, urgente, che la mano applica intensamente sulla superficie, come se cercasse la saturazione, così come quella dimensione quasi scultorea che scatena gradualmente, vibrando nei molteplici spazi che genera e che, come le pieghe di Leibniz, ci trasporta in un universo di sensibilità artificiosa. Nello stesso modo in cui il colore acquisisce il suo spessore, lascia indovinare la possibilità di un inconscio scultoreo che percorre dall’interno tutta la sua pittura, come se si legasse tutta tra sé, attraverso questi diagrammi fatti di nodi borromei (di cui Lacan ci ha parlato), che sottolineano la dimensione inconscia che di fatto sembra abitarla.

3. L’immagine della moltitudine

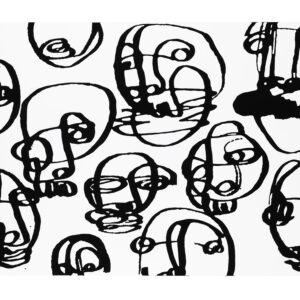

Se, a prima vista, la fluidità delle linee è organizzata come uno spartito musicale e la sua notazione sulla superficie del dipinto suggerisce una scrittura animata di segni apparentemente destinati a essere tradotti in suoni, subito dopo suggerisce la presenza animata di figure, numerose figure che si direbbero nate da un graffito di strada in una delle nostre città, suggestioni di una folla che, come nei manifesti politici, fa sorgere davanti ai nostri occhi quello che riconosciamo come immagine della moltitudine. In tal senso questa è un’arte intensamente urbana, contemporanea, vibrante, suggestiva, animata da questa sottile tensione geroglifica che nell’immediato non sappiamo come decodificare, poiché attraverso di essa appare una trama intensa, indecifrabile e persino frattale.

Così come accade di fronte ai drippings di Pollock potremmo dire, di fronte a questi movimenti di colore e dei gesti che li animano, che essi corrispondano a impulsi che riverberano grazie alla presenza immediata di quello stesso gesto, le intensità di danza di un corpo. Quasi convulsive, poi, come conseguenti all’urgenza del performer che, sulla tela in bianco — lo schermo — lascia svilupparsi trame complesse, movimenti impulsivi, sismografici, di una rivisitazione attuale dell’action painting, cercando di fissare, in questa velocità impetuosa, una specie di movimento automatico della sensazione.

Tuttavia, subito dopo, e grazie alla nostra abitudine di vedere e osservare, capiamo che queste forme micro-gestuali sono anche delicate suggestioni figurali, che evocano la complessa trama delle figurazioni dense di António Saura, il grande artista spagnolo le cui figure arrivano da una notte abitata dai fantasmi della danza — del cante jondo e del flamenco — i cui movimenti contratti tornano in scena in figurazioni dal senso quasi drammatico. Ma questo movimento della linea, subito dopo, suggerisce un collegamento remoto con il gesto interrompente di Burri, o con le linee strappate sulla tela da Lucio Fontana.

Nel suo momento egizio, queste di fatto convocano moltitudini, ma davvero, moltitudini di figure provenienti da riferimenti multipli, eruditi e popolari, che potremmo giudicare distanti tra di loro ma che, tuttavia, evidenziano la capacità, nello stesso volteggiare della linea, di chiamare a sé i ricordi di Clifford Still, così come il nervoso registro della linea arcaica sui muri, che ci ha insegnato la fluente pittura di Cy Twombly.

Tutto, infatti, nell’opera di Danilo Bucchi è allo stesso tempo registro automatico e impetuoso di un’enigmatica “conoscenza dagli abissi” — quella connaissance par les gouffres di cui parlava Henri Michaux — forma animata di quello che potremmo designare come vestigio di una gestualità danzante, senza pretese e dal carattere per così dire nietzschiano, dal momento che sembra essere tutta costruita come memoria di una danza dello spirito stesso o, più semplicemente, come un movimento liberatorio della mano su un muro. Analoga, quindi, a quell’altra che il giovane graffiter che cammina nella notte delle nostre città lascia inscritte, come segno di vita o come traccia per tutti coloro che passano davanti ai muri che nascondono le case.

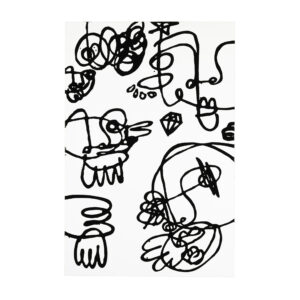

Arte di strada e arte erudita, quella di Danilo Bucchi cammina tra registri che misteriosamente collega e abbraccia in un’unica capacità di fissare come impetuosi registri compositori, concreti, della vita stessa: in questo senso la sua è un’arte poetica, più che un’arte di pittura, poiché in molti aspetti ci sembra che l’ordine della poesia preceda l’ordine dell’immagine.

4. L’impero dei segni

È in questo incrocio che forse troveremo la chiave più esatta per l’enigmatico universo plastico di Danilo: tra poesia e pittura, tra scultura e gesto, tra segno e simbolo, la sua arte accenna, da lontano, a un altro campo che forse ci è meno evidente: l’immagine fotografica, pratica che ha ugualmente sviluppato.

In una serie che ha realizzato, Japan Diary e che rimane inedita, l’Artista ha chiarito i suoi processi e possiamo quindi capire in cosa consiste ciò che, secondo Deleuze, potrebbe essere designato come la sua formula, ovvero, in un registro sintetico, esattamente diagrammatico, in cui l’immagine fotografica innesca un’idea dello spazio urbano che poi riemerge nella sua pittura come già sintetizzato. Infatti, nella sua opera plastica, Danilo Bucchi cerca di formulare immagini sintetiche capaci di comunicarci intensità, impulsi, segnali di carattere quasi grafico, di ciò che è la scrittura della vita nelle città, che lui capta alla maniera del flanêur baudelaireano.

La visione della città appare come sintetizzata, o meglio, diagrammata, come se partisse dalla condizione di essere solo un foglio bianco su cui una varietà di segni multipli e chiusi potrebbe essere inscritta: tutto sembra organizzarsi nelle strade, nelle piazze, negli spazi pubblici, che siano edifici o muri, viali o giardini, come se obbedissero a una stessa logica impulsiva nata dal movimento stesso della vita, scrivendo se stessi sullo spazio urbano.

I suoi riferimenti pittorici, che ho menzionato sopra, gli servono non tanto come modo per incorporare citazioni erudite, ma piuttosto come elementi che gli consentono di accedere alla costruzione di un linguaggio proprio, quasi un alfabeto, suscettibile di trascrivere, in una scrittura veloce, vibrante, elegante, urgente e intensiva, una visione del mondo.

Infatti, la sua dimensione geroglifica — alla quale ho accennato prima — acquisisce forza ai nostri occhi, così ci rendiamo conto che, grazie a essa, siamo portati a presenziare, come davanti a un grande schermo, a un’esperienza analoga a quella che ci offre essere in possesso di una forma di scrittura.

Così, come nel carattere giapponese, il cui significato è allo stesso tempo grafico, visivo e sintagmatico, anche qui si direbbe che, quasi alla maniera del grande Saul Steinberg, tutto è organizzato secondo una logica pittorica fluente e per alcuni aspetti simile a quello che presiede la costruzione dell’incisione giapponese di Ukiyo-e.

Ma, nell’opera di Danilo, queste immagini che evocano il carattere orientale, acquisiscono ora una dimensione scultorea. L’artista ha scelto di passarli a una tridimensionalità attraverso ritagli operati su legno che poi dipinge e che può montare direttamente sulla parete, dove ogni figura riappare come su un pannello dipinto. Figure libere nello spazio, che transitano dal disegno e dalla pittura per entrare nella dimensione scultorea, servono ora a riattivare il senso musicale dell’intera opera, a cui ho accennato sopra. Generando una specie di danza, popolando le pareti in cui si accoglie la sua esposizione, sono figure vive di questo movimento che lega l’opera di Danilo Bucchi a un nuovo sentimento che si potrebbe definire da orientalista. Tutto acquisisce la dimensione del movimento, della fluttuazione, della dinamica dei segni quando sono liberati dal significato immediato e consegnati solo alla variabilità del suo essere-segno.

Geroglifici, saltano dai dipinti per invadere i muri, come graffiti per le strade delle nostre città, animati quasi da una vita propria e poetica, creature di sogno e di fantasia che danzano liberamente negli spazi e che alludono a un tempo mobile, che evoca questa modernità liquida di cui ci parla Zygmunt Bauman e nel cui regime tutti ci imbattiamo in una realtà commovente, mai fissa, fluente e segnata dalla dissoluzione della precedente immagine che avevamo del mondo come un solido.

Così qui ritroveremo i ritmi sensibili di questi “ritratti del mondo fluttuante” che hanno fatto la gloria dell’arte giapponese a partire dal XVII secolo, le cui intense rappresentazioni della vita urbana avrebbero segnato, due secoli dopo e in maniera indelebile l’arte dell’occidente a partire da Manet, generando nuove e inaspettate forme di rappresentazione che hanno portato alla nascita della Modernità.

Tutto qui è mobile, intenso, allo stesso tempo sismico e segnico, suggerendo un’apprensione della vita analoga a quella che Roland Barthes ha appreso in Oriente e che poi ha chiamato l’impero dei segni proprio per designare questa coincidenza estrema tra vita e linguaggio che gli sembrava differenziare la cultura orientale da quella occidentale.

La pittura di Danilo Bucchi è un cinema: di fronte a lei, dobbiamo solo lasciarci trasportare dalla sua intensa narrazione, per la fluidità dei suoi gesti, segni, note, per il modo in cui, vibrante, trascrive in una scrittura tutta sua, il nuovo ordine poetico che attraversa il nostro tempo.

Bernardo Pinto de Almeida

Marzo, 2023

The sound of painting

- Rhymes, rhythms

Danilo Bucchi’s work, the immediacy of which makes it appear simple, nonetheless presents complex conceptual problems. First and foremost, there’s a challenging question: how can we convey painting beyond the rigorous models of that which is visible and, at the same time, tether it to the perception of its volume in terms of its tactile, almost sculptural dimension, as well as to our reminiscences of music and rhythm, so that we might unearth its musical aspect?

Indeed, for his multiple expressions — installation, photography, painting or even in works of a digital nature — the artist always reverts to a process that we can define as being rhythmic in nature, which allows us to perceive his intense relationship with musical notation. That is the way in which every gesture, every sign, every movement of the body – because we what we’re really talking about are the body’s gauges – which is projected onto the surfaces and which we find continuously in his work, is highlighted as a form of gesturing similar to improvisation, to musical notation and even to concrete poetry. This, together with the ability to move towards John Cage’s games of chance, reveals a major performative indicator: as Achille Bonito Oliva said in this regard, “Beyond, there are the unexpected aspects of life and forms in his creativity”.

Hence, what we immediately perceive upon first coming into contact with his work invariably refers us to a perceptive sense which, through our body, we understand also originates from the movement of another body, almost functioning as if it were in a performative dimension. Indeed, the artist’s work, his elegant and subtle gestures, which we almost view as being like a style of writing – which, on an erudite level, is reminiscent of Cy Twombly, as well as of Henri Michaux, and which also dialogues, on another level, with the graffiti that floods the streets of our cities — presupposes, in its execution, the performative movement of the body and the strong inscription of gesturing in the painting, which tends to immediately ascribe it to the occurrence.

That’s because, in reality, however discreet and almost capricious this gesturing may seem to us, with its structuring of spaces whose nature is, so to speak, baroque, implies an association with the space of painting that requires the body to perform its own gestures, in improvisation, capable of an inscription movement which, as Bonito Oliva had so profoundly understood, transports it to a dimension which is, above all, vital. It also determines, in its communication, an almost invisible, yet sensitive presence of a structure of rhythms and rhymes that continuously lead the forms of the drawing out of themselves, generating an ambiguous space, since it is populated by a kind of feverish calligraphy.

The practice of a poetic order that in reality draws his work, albeit distantly, closer to the great tradition of automatism which, from Mirò to Pollock and from Henri Michaux to Jean Dubuffet and later to Alechinski, defined a new form of relationship between images and signs, between painting and writing, a powerful relationship based on the notion of rhythm that the 20th century continuously reintegrated, understanding the need to revert to the archaic source, or even the hieroglyphic point of reference.

- The Egyptian moment

It was the Italian philosopher Mario Perniola who began insisting on the possibility of an effect and also of an Egyptian moment in art and society, to try and explain some of the typical signs of contemporaneity by noting, through this designation, the simultaneous presence of multiple temporalities cohabiting in the present time, which the philosopher also considered a characteristic of archaic Egyptian culture: “If everything can be moved back, nothing is current, and likewise everything is repertoire, because everything can immediately become the present[1]”.

Hence, we can say that Bucchi’s work inscribes part of the order of an Egyptian moment, since presences mysteriously converge within it that not only connect it to its own time – particularly in the ways in which it assumes the relationship with photography, languages of installation and even the intensities of the digital expression —, but also dialogue with numerous other visual sources.

That is how his works subtly link to countless artists of various centuries before ours, the current one: as mentioned above, from Baroque art to the 20th century, there are many connections since his work has unexpected relationships with Pollock, Saura, Michaux, Dubuffet and even with current urban graffiti.

However, why mention Baroque here? If we pay a little attention to its internal method of construction, we can immediately see that Bucchi’s work continuously inscribes these variations, almost like watermarks, in which the line develops as if it were dancing in the entire space at its disposal. If, according to Wolfflin, the line was more a typical sign of classicism than of Baroque, being the result of the mark, the fact is that in these numerous lines moving incessantly in his work, in a gesturing that hesitates between the figure and the purest abstraction, the artist makes the suggestion of the mark appear, from the nervous impulse of this movement. Not so much because he seeks the mark, but because it makes itself appear, albeit continuously hesitant among the blacks and whites.

Baroque is, therefore, this nervous, urgent shimmering that the hand intensely applies on the surface, as if seeking saturation, like the almost sculptural aspect that it unleashes gradually, vibrating in the multiple spaces it generates and which, like Leibniz’s folds, transports us into a universe of artificial sensitivity. In the same way in which colour acquires its thickness, it suggests the possibility of a sculptural unconsciousness that runs through all of his painting from within, as if it were all tied together, through these diagrams made of Borromean knots (mentioned by Lacan), which underline the unconscious aspect that in reality seems to inhabit it.

- The image of the multitude

At first glance, the fluidity of the lines is structured like a musical score and its notation on the surface of the painting suggests the animated writing of signs apparently destined to be translated into sounds. Immediately afterwards, it suggests the animated presence of figures, numerous figures that would seem originate from some street graffiti in one of our cities, suggestions of a crowd which, as in political manifestos, cause what we identify as the image of the multitude to arise before our eyes. In this sense, this is an intensely urban, contemporary, vibrant, suggestive art form, animated by a subtle hieroglyphic tension that we aren’t immediately able to decode, since it displays an intense, indecipherable and even fractal texture.

Just as happens when looking at Pollock’s drippings, we could say that, when faced with these movements of colour and the gestures that animate them, they correspond to impulses that reverberate thanks to the immediate presence of that same gesture, a body’s intensities of dance. Almost convulsive, as a result of the urgency of a performer who, on a blank canvas — the screen — allows the development of complex plots, impulsive, seismographic movements, of a current reinterpretation of action painting, trying to establish, at this impetuous speed, a kind of automatic movement of sensation.

However, immediately afterwards, and thanks to our habit of seeing and observing, we understand that these micro-gestural forms are also delicate figural suggestions. They evoke the complex texture of the dense figurations of António Saura, the great Spanish artist whose figures come from a night inhabited by the ghosts of dance – of the cante jondo and the flamenco – whose contracted movements return to the scene in figurations with an almost dramatic slant. However, this movement of the line, immediately afterwards, suggests a remote connection with Burri’s interrupting gesture, or with the lines torn on the canvas by Lucio Fontana.

In the Egyptian moment, they actually gather multitudes, truly multitudes of figures originating from multiple, erudite and popular references, which we could view as distant from each other. Nevertheless, they highlight the ability, in the same fluttering of the line, to attract the memories of Clifford Still, as well as the nervous register of the archaic line on walls, which taught us the flowing painting of Cy Twombly.

Indeed, everything in Danilo Bucchi’s work is simultaneously an automatic and impetuous register of an enigmatic “knowledge from the abyss” — that connaissance par les gouffres of which Henri Michaux spoke — an animated form of what we could call the vestige of dancing gestures, unpretentious and with a so-called Nietzschean nature, since it seems to be entirely constructed as the memory of a dance of the spirit itself or, more simply, as a liberating movement of a hand on a wall. The same, therefore, as the other that the young graffiti artist who walks our cities in the night leaves inscribed, as a sign of life or as a trace for all those who pass by the walls that hide the houses.

Street art and erudite art, that of Danilo Bucchi walks between registers which he mysteriously connects and embraces in a singular ability to establish as concrete, impetuous composer registers of life itself: in this sense, his is a poetic art, more than the art of painting, since in many respects it seems to us that the order of poetry precedes the order of image.

- The empire of signs

It is in this intersection that we may find the most exact key to Danilo’s enigmatic plastic universe: between poetry and painting, sculpture and gestures, signs and symbols, his art hints at another field from afar, one that is perhaps less evident: the photographic image, a practice which he also developed.

In a series that he produced, called Japan Diary and which remains unpublished, the artist clarified his processes and we can therefore understand what consists of that which, according to Deleuze, could be designated as his formula, that is, in a synthetic register, precisely diagrammatic, in which the photographic image triggers an idea of the urban space which then re-emerges in his painting as already synthesised. Indeed, in his plastic work, Danilo Bucchi tries to formulate synthetic images capable of conveying intensities, impulses, signals of an almost graphic nature, of what is the writing of life in the cities, which he captures in the style of the Baudelairean flanêur.

The vision of the city appears synthesised or, rather, diagrammed, as if commencing from the condition of being only a blank sheet on which a variety of multiple, closed signs could be inscribed: everything seems organised in the streets, squares, public spaces, whether they be buildings or walls, avenues or gardens, as if obeying the same impulsive logic born of the very movement of life, writing themselves onto the urban space.

His pictorial references, which I mentioned above, serve not so much as a way for him to incorporate erudite quotations, but rather as elements that allow him to access the construction of his own language, almost an alphabet, capable of transcribing a vision of the world through rapid, vibrant, elegant, urgent and intensive writing.

Indeed, the hieroglyphic dimension – which I mentioned earlier – acquires strength in our eyes, so we realise that, thanks to it, we are led to witness, as if looking at a large screen, an experience that’s similar to the one being offered that possesses a form of writing.

Hence, as in the Japanese character, whose meaning is at the same time graphic, visual and syntagmatic, we could also say here that, almost in the style of the great Saul Steinberg, everything is structured according to a flowing pictorial logic and, in some respects, similar to that which presides over the construction of Japanese Ukiyo-e engraving.

However, in Danilo’s work, these images that evoke an oriental character now acquire a sculptural aspect. The artist chooses to confer three-dimensionality to them through cut-outs made of wood, which he then paints and which he can mount directly on a wall, where each figure reappears as if on a painted panel. Figures that are free in space, which move from drawing and painting into the sculptural dimension, now serve to reactivate the musical sense of the entire work, which I mentioned above. Generating a kind of dance, populating the walls on which his exhibition takes place, they are living figures of this movement that ties the work of Danilo Bucchi to a new sentiment that could be defined orientalist. Everything acquires the aspect of movement, of fluctuation, of the dynamics of signs when they are freed from immediate meaning and consigned only to the variability of its being-sign.

Hieroglyphs leap from the paintings and invade the walls, like graffiti on the streets of our cities. They are almost animated by a poetic life of their own, creatures of dreams and fantasy that dance freely in the spaces and allude to a mobile time, which evokes the liquid modernity that Zygmunt Bauman recounts and in whose regime we all come across a moving reality, never fixed, flowing and marked by the dissolution of the previous image we had of the world as a solid.

So, here we will find the sensitive rhythms of these “portraits of the fluctuating world” that have contributed to the glory of Japanese art since the seventeenth century, whose intense representations of urban life would, two centuries later and indelibly, mark Western art starting with Manet, generating new and unexpected forms of representation that led to the birth of Modernity.

Everything here is mobile, intense, at the same time seismic and sign-based. This suggests an apprehension of life similar to the one Roland Barthes learned in the East and which he later called the empire of signs in order to designate this extreme coincidence of life and language, which he believed differentiated Eastern from Western culture.

Danilo Bucchi’s painting is a cinema: in its presence, we just have to let ourselves be carried away by its intense narration, by the fluidity of its gestures, signs, notes, by the way in which it vibrantly transcribes the new poetic order of our time using its own writing style.

Bernardo Pinto de Almeida

March, 2023

[1] – Perniola, Mario. Enigmas – O Momento Egípcio na Sociedade e na Arte. Bertrand, Lisboa, 1994, p. 127. (Transl. by Chiara Mancini)